There is absolutely no excuse

A shocking, yet unsurprising incident in Germany shines a light on our failure to eliminate misogyny from modern football.

One of the inconveniences of trying to run a nostalgia-driven newsletter called Unmodern Football from a left-leaning perspective is having to walk the fine line between appropriate wistfulness and undue glorification of the past.

There are things about the olden times that were really, really not good. When it comes to some of them, we seem to be stuck in the past. Misogyny, for example.

I wish my second newsletter could’ve been about something else, but recent events simply cannot be ignored – not if you love this game.

During the 3. Liga game between SC Verl and RW Essen, Germany’s only female referee at men’s professional level, Fabienne Michel, made a mistake. As referees tend to do, male or female.

This explains why Essen fans were unhappy with her performance (are fans ever happy with a referee?).

It does not explain – let alone justify – what happened after, as reported by sports journalist, podcaster and author Nora Hespers for sportschau.

Essen fans chanted “Wh*re, wh*re”

Essen fans chanted “The blonde will be f*cked olé olé”

Essen fans called her a slut

Essen fans sang a song demanding her to perform oral sex

Let me be very clear.

We cannot gloss over this one and simply revert to business as usual.

Yes, every referee gets their fair share of vilification – and to a reasonable extent, that comes with the territory of competitive sports in front of a passionate, fanatical live audience. At worst, it has real-world consequences, see: Babak Rafati.

But this was different. Fabienne Michel wasn’t insulted as a referee. In fact, let’s not belittle it by calling it “insults”. That was an assault. She was attacked for being a woman. It was serious, targeted, verbal sexual abuse.

And sadly, the sexual abuse is just one part of the story. The other part? Nobody seemed to care.

Initially, there was barely any coverage. One local newspaper mentioned the chants, called them “tasteless”, and moved on. The incident only gained traction on social media after Nora Hespers shared her article on BlueSky, and only then did some media start picking up the story. Too little, too late. The DFB has since launched an investigation.

Fabienne Michel is not the first female referee to experience verbal sexual abuse, but it’s possibly the first time we’ve seen this level of attacks in Germany.1

Were the scenes in Verl shocking? Yes. Surprising? Not really.

It’s tempting to frame the incident as a freak occurrence. But that doesn’t do it justice. We have to be honest. It’s part of a bigger picture.

So how do you talk about this without sounding preachy? Without grandstanding? Without being self-righteous?

Maybe by sticking to the cold, hard truth.

We are nowhere close to where we’d like to be – where we should be – when it comes to tackling misogyny in football. Obviously there’s been some progress in the past decades, but it hasn’t been nearly enough.

According to a 2024 Kick It Out campaign, 52% of female fans face sexist behaviour or language on matchdays. Their research shows that 42% of regular female fans experienced sexist behavior, such as questioning their football knowledge, wolf-whistling, or outright harassment. 60% of women have heard sexist behavior dismissed as "banter". And some even reported experiencing inappropriate touching, physical violence, or sexual assault. At the same time, 85% of those who had experienced or witnessed sexism or misogyny said they never reported the abuse, “because they didn’t think it would be taken seriously or make a difference.”

A 2023 study highlighted “the escalation of gender-based violence on social media against women players. Four key themes emerged from the netnography: 1. Sexism: the place of women in football; 2. Misogyny and hatred of women; 3. Sexualisation of women; 4. Demand for a male-only space. Sexist comments were apparent in all of the TikTok posts containing female football players, with some also containing more aggressive misogynistic comments. Other dominant comments sought to reduce women to objects of sexual desire and belittle their professional skills, whereas others were appalled at the presence of female players on the clubs’ official accounts, demanding them to be a male-only space.”

This isn’t only a football problem. It’s a societal one. But football needs to keep up with progress made in other parts of society. In their book Fußball als Soziales Feld (Football as social field), Thole and Pfaff state that “the collective fan cultures and practices surrounding soccer seem to offer a special arena for the performance of social power relations and the exercise of discriminatory acts such as racism, sexism and homophobia”.

An experiment involving 613 participants evaluated perceptions of elite female and male footballers. When the players' gender was visible, men's performances were rated higher. However, when the gender was obscured by blurring, the ratings of female and male athletes showed no significant difference.

So much in our football culture is still rooted in backwards thinking. The attacks on Fabienne Michel are just the tip of the iceberg.

Take the perpetuation of male or manly stereotypes. When the Essen manager describes the performance of his players as “very manly”. When players are hailed as “tough” for carrying on after a head injury. When we call our rivals “H*rensohn” (=son of a wh*re). Small things, maybe, at face value. But they are all part of the problem. What is the reverse of calling a tough player “manly”? Exactly.

Take the social media pile-on under a social media post quoting Giulia Gwinn who criticized the Bayern board for missing their cup semi-final. When dozens of men comment that nobody wants to see women play football. When they comment that women expect too much. When they even say that women shouldn’t be playing football in the first place. That’s part of the problem.

Take rape and domestic violence allegations. When a huge chunk of fans instinctively side with the accused instead of the victims. When “innocent till proven guilty” is not applied to the victim making the accusations, just the accused. When fans still side with the perpetrator even though there is proof. When they make light of sexual abuse and violence. When convicted players still get contracts. When too few people care. That is part of the problem.

All of this adds up. It creates a culture where women feel unwelcome. Where sexist abuse is normalised. Where female players are dismissed. Where a female referee is verbally assaulted for being a woman – and nobody steps in.

Maybe the extent of what happened in Verl is a shocking outlier, but it’s the sum total of every little bit of everyday sexism that lays the foundation for this kind of incident.

There is absolutely no excuse not to try and facilitate change. Unfortunately, it’s not only the terraces where women face bigotry, despite making up at least 40% of German football fans. Eva-Lotta Bohle is one of them. A passionate football fan who hardly misses a game of Arminia Bielefeld – and freelance journalist slash beloved podcast pundit (11 Freunde and others).

Eva:

“As a woman who mainly reports about men's football in different ways, I do not think that men sometimes understand what kind of comments and ‘feedback’ women in sports get because of the misogynistic bias. And I want to be clear: Sexism is not only shown in insults but also in comments towards a woman's appearance. When I do a sports show and men comment: ‘Well she is pretty’ or ‘does she have a boyfriend?’, that's sexist. It is not a compliment. It does not concern my work. And nobody does that in return towards men. When I say something that is wrong, people do not only correct me but they put that into context with my gender.”

It doesn’t help that other journalists, especially men, do not offer the needed support.

Eva:

“Some men do not want to understand the basic concepts of patriarchy, which was made very obvious due to the recent Fabienne Michel-incident. The people who have to do the job and report the problem are women. Criticism will often be declared as ‘hysterical’ or ‘too woke’ just because men can't accept that they're wrong and there is no equality yet.”

Eva won’t leave the football scene anytime soon, but these experiences do take their toll. She notes: “That has an impact on how I work – more in the past than it has now, but it's still there.”

Sexism is one of the reasons we lose female referees, says Nora Hespers in her op-ed for sportschau. One in three women drops out of the referee training programme. One in five men does. That stat alone should set off alarms.

And it’s not only referees. This applies also to female fans and players. "It starts at birth … by the time they reach puberty they are already in the mindset that this isn’t really where I belong", says Lisa West from Women in Sport.

Excluding women from football spaces is a huge problem.

Mara Pfeiffer is a writer. A sports journalist. A devoted Mainz 05 fan. She loves football – and more to the point, she knows what she’s talking about. That’s why she’s part of the crew that launched a podcast with Rebecca van der Meyden and Kristell Gnahm six years ago. Most of the reactions to the podcast were positive – from women, yes, but also from men. Echoing Eva’s experience as a female football expert, the group of women also got unwarranted pushback.

Their mistake? They decided to talk about football while being women.

The backlash was as predictable as it was pathetic. Not because of anything Mara and her team said, but because women dared to say it. No real critique. No factual disagreements. Just the usual mix of condescension and insult. As if discussing football required a Y chromosome. One particularly egregious example stood out, where male podcast hosts deemed it a good idea to rate the women based on perceived “f*ckability”.

I asked Mara what kind of solidarity she’d like to see from men in moments like that.

Mara:

“I wish for a kind of solidarity that doesn’t depend on sexist incidents to occur first – one that isn’t merely reactive, but becomes second nature. That includes taking the time to educate oneself: ‘What are sexist structures? How might I be complicit in them, perhaps unintentionally? What can I do to change that?’, instead of constantly deflecting and insisting it has nothing to do with you. It means meeting women in football – and everywhere else – on equal footing. That might sound self-evident, but sadly it still isn’t. It means, for example in the context of sports journalism, actively considering them, acknowledging their work. Bro-culture in sports journalism is also revealed in the way praise is primarily exchanged among male colleagues, while the work of female peers remains largely invisible. Solidarity is not silent. It requires speaking up – even when it’s uncomfortable – for instance, when a colleague makes a crass remark, rather than brushing it off afterwards with the usual lines about how ‘making a fuss’ over it isn’t what women, or equality, or feminism really want. Solidarity means understanding this: men, as a rule, have the option of whether or not to engage with the issue of sexism. Women and others do not.”

The last two sentences really hit me. Definitely something to think about.

Has she witnessed any progress in the past six years? Are things getting better?

Mara:

“My impression is that this runs fairly parallel to other societal developments: on the one hand, some things have improved – there’s greater awareness, there are initiatives such as the network against sexualised violence in football, of course F_in or FKM, and there are groups as well as individuals doing a great deal to bring the issue onto the agenda.”

Eva weighs in with a reason for the improvements:

“There are more women in the stadium in general, there are more opportunities to connect with one another, and that is something that I consider a positive change because women want to take their place.”

But there’s still work ahead, as Mara mentions:

“At the same time, resistance to these issues hasn’t subsided – if anything, it may even be growing stronger in the wake of current backlash tendencies. And from my perspective, there’s a trend emerging where sexism seems to need to appear overly crude or violent in order to be recognised as such, while structural sexism continues to be dismissed or downplayed in many instances. And that’s a problem.”

Case in point: It took RW Essen over a week to put out a, in my opinion, tepid public statement (and some of the fan pundits seem more worried about the fallout than the incident itself).

My honest opinion: I think we – as in: men – have failed, in that we haven’t succeeded in making the game more inclusive for women. This is not about individual guilt. It’s about what we can do better. It’s about responsibility.

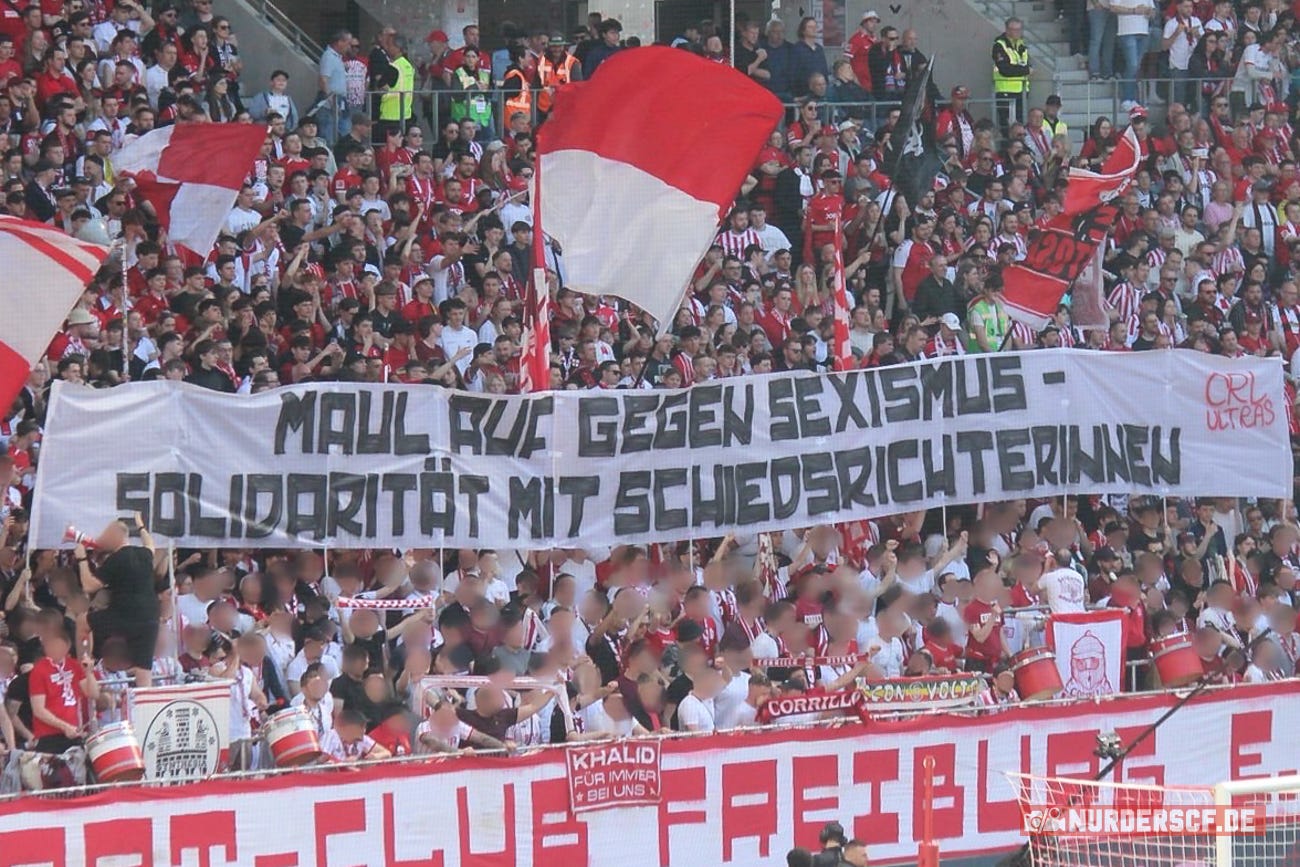

Every one of us can make a difference. Arguing with strangers in Instagram comments won’t fix football. But it’s a start. Checking our own blind spots? Definitely a start. Calling out misogyny in our group chats? A start. Telling the guy next to us on the terraces to shut it when he insults a woman? A start.

Eva, who mostly visits men’s games, highlights the importance of speaking up when talking about her personal experience on the stands:

“I have a group of people around me that is my safe space. I know I can rely on them, I know that when somebody is being sexist we say something, and that is huge, personally.”

But not everyone has this kind of support, she adds:

“Experiences differ. Boundaries differ, and so does the perception of discrimination. Only because I have the feeling that I can go to home and away games, and don’t experience a lot of sexism towards me, it doesn't mean that it does not happen to other women or that it is completely gone.”

And it’s not just about verbal or behavioural discrimination. Structural sexism is a problem, too.

Eva:

“No matter if home or away, there are always less toilets for women in the stadium. Sometimes, there are no bathroom bins for menstrual hygiene products, no running hot water etc. Furthermore, the entrance situation is completely focused on men: Women often have to stand in the security line for men, then get their ticket scanned before going through security checks themselves. Separate entries for women are mostly never available, no matter what league you're in.”

This is an aspect a lot of us tend to oversee. And it will take more than a couple of performative gestures from clubs to overcome these barriers.

When it comes to the Essen incident specifically, I asked Nora Hespers whether she has suggestions how it could’ve been handled better, especially by the club and other officials.

Nora:

“From the club’s perspective, it would of course have been important to face the facts from the outset and take a public stance. RWE didn’t do that. It took nine days before a public statement was made on television – and even then, not to sportschau, the outlet whose investigation had triggered the issue. At the same time, a written statement was released. In it, the club declares that, according to its statutes, it firmly opposes all forms of discrimination. In my view, that doesn’t quite align with the delay in responding. What’s also crucial in such cases: once the allegations become known, the clubs should be reaching out to the referee involved. It would also be worthwhile to ask how referees – and female referees in particular – can be better protected in future. Or more broadly, how women can be better protected from sexism in stadiums. That would clearly signal an awareness of the problem. In many clubs in the 1st and 2nd divisions, for example, there are now awareness teams. These are usually deployed by fan organisations and act as contact points when issues arise – whether it’s sexism, sexual assault, ableism, queer- or transphobia. In the 3rd division, such awareness teams are not yet widely established [Editor’s note: Arminia Bielefeld is a positive example]. Here too, based on recent experiences, clubs could take action and signal their intention to actively support fan work through awareness teams in the future. Because regardless of the outcome of any possible investigation, the incidents clearly show: there is a problem.”

Cue the obligatory “keep politics out of football” comment. Look, if that’s what you want there’s an easy fix. Everytime we ignore or even participate in misogyny in football, we are the ones who put politics in football. So yeah, we know what needs to be done.

I don’t think we need to be perfect. Just better. Progress, not perfection, as Denzel Washington says in The Equalizer.

I’m not asking for a sanitised version of football. We love the grit. The chaos. The emotion.

Rivalry, outrage, sh*thousery, creative, tongue in cheek insults. That’s what makes football football.

But there’s banter. And then there’s outright discrimination.

Eva agrees:

“The German language has so many fantastic ways to tell someone else that they're sh*t – I do believe that, in theory, non-discriminatory banter is possible. There are two problems though: People use curse words without knowing the hateful background – like F*tze, H*rensohn – and it's a difficult task to explain to them why it is problematic. But the bigger problem is people who use these insults because they discriminatory. You won't get them to change.”

So it’s up to us to be a vocal majority and exclude those trying to keep women out of the sport.

Because if there’s one area where modern football could actually shine, it’s this: Creating a space where everyone feels at home. But we’re not there yet.

Right now, 77% of female fans say they feel safe at matches – despite the abuse they’ve faced.

Let’s get those numbers up. Let’s make it a positive experience for all of us. There’s absolutely no excuse.

Since penning the first draft of this article last weekend, there has been more coverage, and many have come out in support, condemning the incident. At the same time, there have been attempts to downplay it.